Swiss Cheese and Early Brain Development

Print This Post

When I want comfort food, I order a grilled turkey ‘n Swiss on rye at my favorite deli. While not all Swiss cheeses have holes, the American Swiss variety typically does. This widely-used holey staple is available in groceries, delis, and supermarkets across the nation.

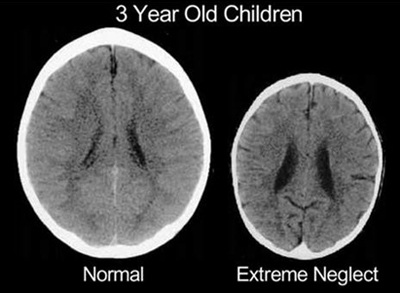

While seeing holes in Swiss cheese is common, seeing holes in brain scans is another story.

The quality of the first relationship of a newborn baby with a parent or caregiver sets the stage for every other relationship that follows. Researcher Paul MacLean termed the huge prefrontal cortices of well-nurtured babies as the angel lobes because they are associated with the highest human qualities.

Not surprisingly, children raised in deprived, unresponsive, abusive, or non-stop stress settings develop brain wiring that reflects negative experiences. Through early brain development research, we know that negative experiences can delay brain development, lead to hyper-reactivity and extreme aggression, and may even cause huge holes to form in areas where higher-level brain functioning should take place.

Even more troubling, scans of violent adults reveal that those holes in the brain that formed during childhood are still there. Unlike a grilled Swiss cheese sandwich where an intervention simply melts away the holes, the adult brain does not repair itself.

This is Brain Awareness Week, an initiative of the Society for Neuroscience that presents an opportunity to ensure that everyone who touches the lives of Georgia’s children—from parents and child-care professionals to policymakers and legislators—understands how adults influence early brain development.

In my work with the Georgia KIDS COUNT project, I’ve learned how critical it is to target resources and programs to young children living in families with incomes below the poverty level. Here in Georgia 23 percent of young children ages 0 to 5 live in households with incomes below the poverty level. Families who experience chronic poverty, homelessness, family illness, and other toxic stresses often do not have the time or knowledge to respond sensitively to young children’s needs. Providing high-quality early education, two-generation programs, and community supports for families in chronic poverty can lessen the effects of toxic stress on young children’s developing brains.

For more information, visit the Better Brains for Babies website and check out a brief, Early Brain Development: Policy Makes a Difference.