Georgia’s Future Economic Vitality Banking on Reaching the Missing 16%

Print This Post

by Krystin Dean

Georgia’s high school graduation rate has increased by 14% since 2012. According to Georgia Partnership for Excellence in Education (GPEE) President Dana Rickman, access to career pathways, more effective use of data to identify and meet students’ individualized needs, and an increasing emphasis on supporting the whole child and creating a positive school climate all have played a vital role.

While this is promising news, Rickman noted that the economic viability of Georgia’s future depends on reaching the 16% of students not graduating, because 60% of jobs in this state will require some sort of postsecondary degree by 2025.

“Only 40 to 45% of Georgia’s adult population has any education beyond high school,” said Rickman. “That’s the talent gap we hear about. We will have more jobs than workers—and there aren’t enough kids in the education pipeline in K-12 who will graduate between now and 2025, even if we graduated every student. So that 16% not graduating on time hurts us.”

Rickman theorized that a large portion of this population has complicating factors like extended absences, foster care, migrant moves, and involvement with the Department of Juvenile Justice—but noted that specific data is not available.

“That lack of data makes it difficult to design interventions to target this population, because we don’t really know what it looks like,” said Rickman. “We have to figure out why these kids aren’t showing up. There are all kinds of reasons—but is there a predominant underlying factor? Community connections and data sharing across multiple agencies can help put that picture together.”

Third-grade reading proficiency is the leading predictor of high school graduation, and the negative impact of absences on literacy is 75% greater for low-income children. Reading proficiency is also a leading indicator of the future workforce.

“If a business is planning 10 years out to grow and doesn’t have a population of kids who can read on grade level, they may as well move,” said Rickman. “So how do you keep them there? You focus on literacy.”

Rickman said a two-generation approach is critical to improving literacy outcomes, high school graduation rate, and Georgia’s economy. According to the Aspen Institute, this approach centers on the whole family to create a legacy of educational success and economic prosperity through generations.

“We’ve got counties, especially in rural areas, where 40 to 50% of the adult population doesn’t have a diploma or anything beyond high school,” said Rickman. “This leads to this two-generation reading problem. If your parent doesn’t read well, it’s very likely that you won’t read well. So, we see this poverty cycle. To break it, we must focus on the whole family.”

Changing the Cycle in Richmond County

Central Savannah River Area (CSRA) Regional Educational Service Agency Executive Director Debbie Alexander worked in the Richmond County School System (RCSS) for 34 years. In 2016, she dug into data with colleagues and found that the same schools continued to struggle—despite district and school leaders’ focused efforts—and sought to build a community-wide effort to engage more partners.

Since then, the county has made significant progress in further exploring multi-dimensional data to understand which factors are contributing to children not learning to read and identify solutions to help all children meet this critical milestone.

“The crisis doesn’t begin when kids come to kindergarten,” said Alexander. “What happens before they ever go to school, what’s happens after school—that entire journey from birth to adulthood—that’s the bigger issue.”

Augusta University and the Richmond County Board of Education received a $100,000 Innovation Fund grant from the Georgia Center for Early Language and Literacy in 2018 to support occupational therapy, virtual learning, student development from birth through pre-K, and other early literacy efforts.

“To make a true change, you have to support parents during the birth-to-3 window because that’s when 80% of the brain is developed,” said RCSS Associate Superintendent Dr. Malinda Cobb. “And you must support the students’ parents to address nutrition, health care, and financial literacy. It takes a multi-generational approach to change the cycle of poverty.”

Stressing the economic impact of third-grade reading proficiency attracted partners like the Metro Augusta Chamber of Commerce, which formed an education committee focused on grade-level reading and helped RCSS launch a Success Center in 2019 to provide academic and wrap-around supports for children.

“The Success Center moved to the Tubman Learning Center during the summer of 2020 so that families could access the resources from a location on the transportation line,” Cobb explained. “While the center serves all of our schools, many schools have set up their own smaller version of a Success Center.”

RCSS’s 2020-2025 strategic map has a focus on early literacy and early numeracy. An Early Learning Department was created with six staff members focused on improving third-grade reading proficiency.

The Augusta Partnership for Children, a Georgia Family Connection Collaborative, has a community team that engages child care, early learning, parental education, and health care partners in this collaborative effort to improve literacy.

“A huge part of our strategy is sharing ideas, and we’re seeing more innovative ideas and programs as people come together,” said Candice Hillman, the Collaborative’s executive director. “We look at the school system’s plan to see how we can further their efforts. We support each other.”

School leaders serve as catalysts for change by openly sharing the school system’s story, enlisting support from the whole community, and having a “birth-to-21 mentality” when it comes to education that ranges from informing parents about how to access pre-K and Head Start programs, to expanding meal programs and health care access, to introducing students to career options well before graduation.

School social workers work closely with counselors to identify students who may potentially drop out and explore early interventions. Their also track down students who already left and look for solutions to bring them back.

“Since the pandemic, we’ve focused more on personalized learning to meet the students where they are and work toward improvement,” said Cobb.

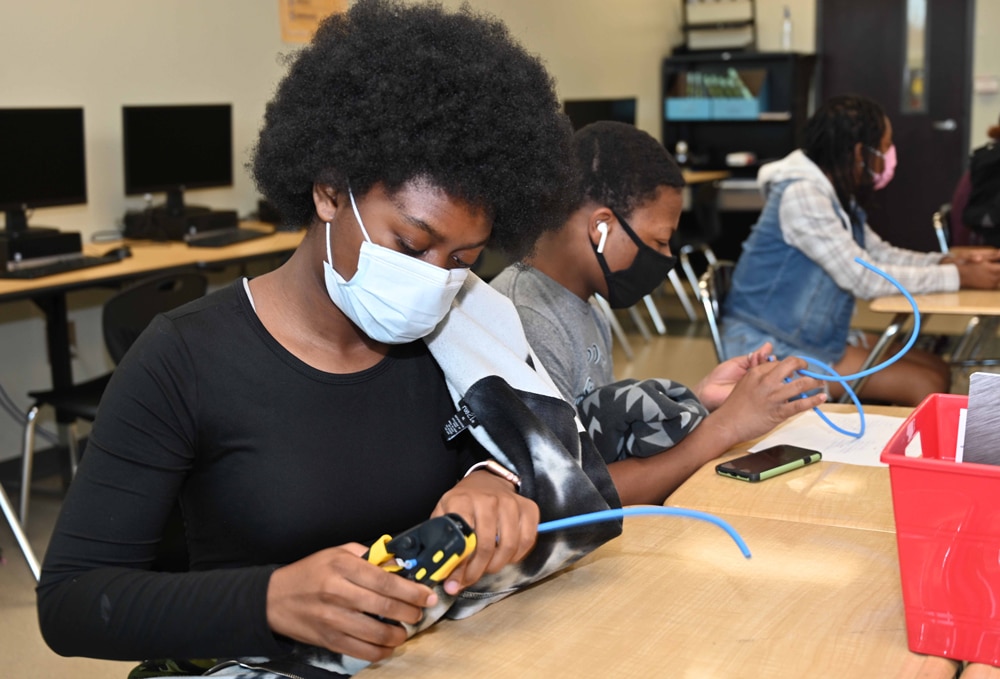

Faith-based partners, the YMCA, and the Boys & Girls Club provide after-school care with tutors and access to technology to support academic excellence, while business partners provide internships to expose students to life after high school.

Alexander pointed out that while some barriers to attendance and academic achievement, such as lack of transportation and health issues are easy to spot, others aren’t always immediately evident.

“A child may become homeless when a parent loses a job, while another child is living with grandparents who get sick or pass away,” said Alexander. “These are things I’ve heard from students. The heart of any school system’s and community’s reaction has to be: where can we meet the needs of individuals?”

Vikki Pruitt, Augusta Partnership’s deputy director, said the Collaborative is always looking for new ways to support parents. “We have to reach parents who dropped out of school, because they can’t help their kids if they don’t know how,” she said. “We have to look at everyone in the household—not just the child who’s struggling. A two-generation approach has a robust vision for family well-being, identifying the essential experiences, supports, and resources necessary for families to survive and thrive.”

Pruitt went on to say that family well-being includes financial, social, mental, and spiritual aspects—and it requires multiple materials, conditions, and systems to be coordinated.

A large portion of the population remains in Richmond County after they graduate, so collaborative efforts focused on the whole family will have lasting benefits.

“When we help students become more literate or well educated, they will in turn have better parenting skills and raise children who are stronger readers,” said Alexander. “Your entire community changes. It’s a beautiful cycle. Someone once said if you can’t help 100, help one. You’ve got to start there. But we can’t keep it small. We have to look at trying to impact the most.”

Contact Candice Hillman at chillman@augustapartnership.org to learn more about the Augusta Partnership for Children and the Collaborative’s two-generation approach to supporting families.

Read and share Expanding Our Perspective, Unlocking Our Potential—Georgia Family Connection’s 30-year impact report.

Contact:

Krystin Dean

GaFCP Communications Specialist

706-897-4711

krystin@gafcp.org

Follow us on Twitter: @gafcpnews

Connect with us on Facebook.