Linking Stable Housing to Child Well-Being

Print This PostCOVID-19 has exacerbated hardships for low-income families who were already coping with unaffordable and unstable housing, often spending more than half of their income on rent and utilities. Renters who live with children have consistently been more likely to be behind on rent than adults not living with children. Research links housing instability, homelessness, and poverty to adverse effects on young children’s health, development, and future school performance. Prolonged or acute hardship in early childhood can permanently affect development of the brain and related systems. More than 1 million children 5 years old and younger encountered homelessness in 2019.

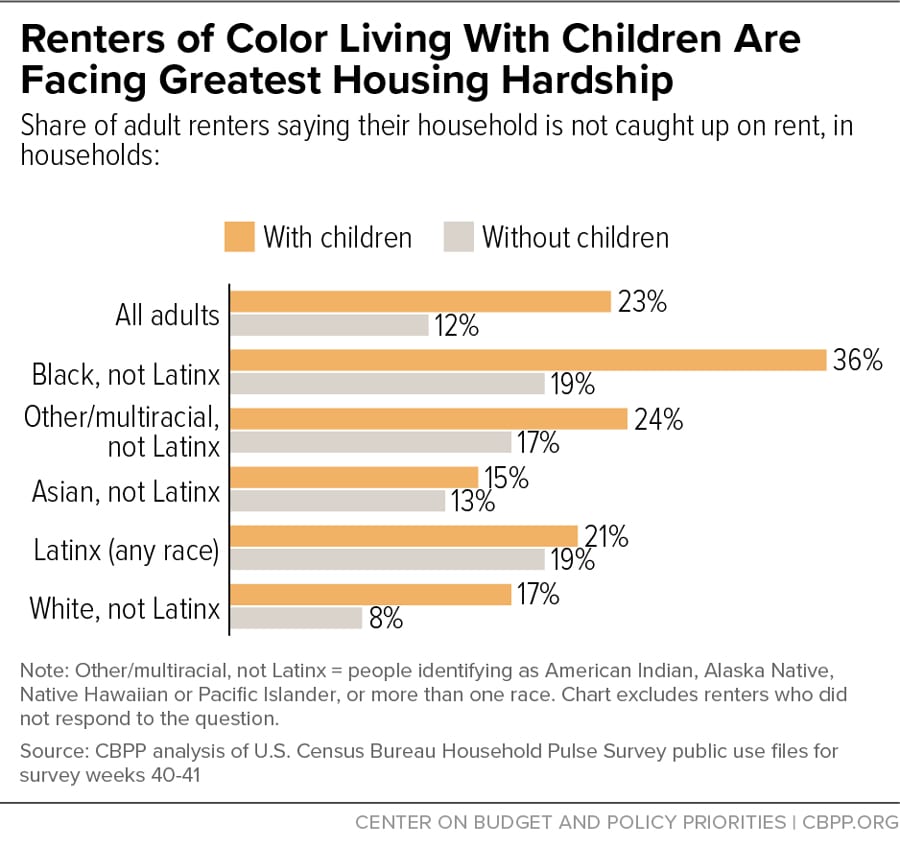

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities Senior Policy Analyst Sonya Acosta points out that housing costs disproportionally impact black and Latinx families nationwide, and that more than half of the families with children who are homeless are black. According to Acosta, a January 2022 survey revealed that 3 million renters with children believed they were likely to be evicted within the next two months.

This research summary:

- provides an overview of the current research on the impact of high rates of housing instability and poor housing quality on child development;

- examines the impact on socioemotional development, academic performance, and cognitive and physical development;

- reviews the relationship between housing stability and availability of quality child care and attendance; and

- provides insight into interventions and preventions that will most support young childhood development.

Housing and Child Development

Research indicates that housing affects children’s physical, social-emotional, and mental health, as well as school achievement and long-term economic attainment. Essential features related to housing include physical housing quality, crowding, residential mobility, homeownership, subsidized housing, and affordability. Communities continue to struggle with how to provide support to families in the midst of the challenges of affordable housing. One in four eligible families nationwide are receiving rental assistance. According to Acosta, housing assistance is largely underfunded, which leads to a lack of housing, poor quality housing, and housing instability. She said communities can help to increase safe and stable homes for children through vouchers and other investments, which also impact positive developmental impacts.

The National Library of Medicine and Acosta point out that housing factors like quality and instability can impact children’s socioemotional development, cognitive development, behavior, and physical health development. And infants who experience homelessness are more likely to develop physical health problems and be underweight. Preschool children have shown attention and behavior challenges when they experience more housing instability and poor quality. Only 25% of the families with children who are struggling with housing receive any subsidy or rental assistance.

Research also reveals that there’s a potential for children and families to adapt to housing instability depending on how frequently and at what age it occurs. Families are able to stabilize and adapt to new environments, which can help explain the rebounds. Some research has indicated that single time moves and short-term family changes can actually support and enhance cognitive development over time. Moves toward stabilization help to promote learning.

Housing Quality

Research has linked housing quality to impacts on children’s physical health. Tama Leventhal and Sandra Newman of the Bloomberg School of Public Health found links between environmental toxins, hazards, and crowding and poor physical health outcomes. With all emergency housing and shelter housing, providing connections to high-quality child care and early education supports to help mitigate the impacts of housing instability or poor-quality housing is essential.

In a longitudinal study of children and youth in low-income neighborhoods, the National Library of Medicine found that poor housing quality was associated with poor emotional and behavioral functioning and lower cognitive skills. It was strongly predictive of children’s well-being across childhood, even more than housing stability. Those who lived in poor-quality housing demonstrated more emotional and behavioral challenges. If housing issues increased over time, so did emotional and behavioral issues. The stress and instability associated with low-quality housing may bring stress to parents, which may contribute to children’s negative socioemotional functioning and overall well-being.

A 2011 study funded by John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur and William T. Grant Foundation followed 2,400 children and families in low-income neighborhoods in Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio for more than six years examining quality of housing and child development and other factors. The National Library of Medicine used data from this study and found that poor-quality housing was related to higher rates of emotional problems, depression and anxiety, and more behavior problems. Children in low-quality housing also experienced lower school success in core subjects.

Veronica Gaitán of Housing Matters—an Urban Institute Initiative also points out that it’s critical to examine housing quality as well as stability, citing research that poor housing quality is related to higher rates of depression, anxiety, and aggression in elementary school and young adulthood. Gaitán tracked data for children in Housing and Urban Development (HUD) supported housing and compared outcomes to children in non-supported housing. Those in supported housing with increased regulation of quality found that children in higher-quality housing had lower rates of blood level levels, and improved health and well-being. These findings indicate the need to ensure that housing quality is addressed while also addressing housing stability.

Housing Stability

Housing stability, according to the National Library of Medicine, is a growing issue in the United States, particularly in urban low-income neighborhoods. Families experience housing instability due to material hardship, satisfaction with living conditions, housing disrepair, and other reasons. Research has shown links between housing instability and academic achievement, emotional regulation, and verbal abilities with outcomes that can persist through adolescence and adulthood. David Wood, M.D., and colleagues, in a 1993 study of more than 9,900 children in the 1988 National Health Interview Survey, found that frequent relocation was associated with higher rates of negative outcomes for children, including repeating a school grade and having four or more behavior problems.

More recent studies have found that housing instability can negatively impact cognitive development regardless of poverty, maltreatment, and other family factors. Here are several of these key studies and the relevant findings, including areas of consistency:

Housing instability impacts cognitive development and educational outcomes. When young children experience greater instability, they have greater impacts on cognitive functioning, verbal and nonverbal abilities, and lower levels of school readiness (Fowler, McGrath, Henry, Schoeny, Chavira, Taylor, and Day; Molborn, Lawrence and Root, 2018; Gaitan, 2019; Anastosio, Leventhal, and Amadon, 2022).

Research indicated that programs like HeadStart and other high-quality early care and education programs can help to mediate the impacts of residential instability among low-income children (Anastosio, Leventhal, and Amadon, 2022).

Housing instability impacts socioemotional development and behavior. Higher levels of housing instability were found to be related to poor behavior outcomes, more attention seeking, and negative externalizing behaviors (Gaylord, Cowell, Hoepner, Perera, Rauh, and Herbstman, 2018; Gaitan, 2019; Molborn, Lawrence, and Root, 2018; Rumbold, Giles, Whitrow, Steele, Davies, Davies, and Moore, 2012).

Regardless of material hardship level, children with housing instability experienced more attention and thought-related behavior problems—concentration difficulties, impulsivity, nervousness, and poor school performance. (Gaylord, Cowell, Hoepner, Perera, Rauh, and Herbstman, 2018; Molborn, Lawrence, and Root, 2018; Gaitan, 2019).

The more moves a child experiences at young ages the greater and more long lasting the impacts on child development. Children with more than three moves are more likely to have attention problems and both internalizing and externalizing behavior challenges, poor education attainment, and a greater chance of dropping out of school (Ziol-Guess and McKenna, 2014; Fowler, McGrath, Henry, Schoeny, Chavira, Taylor, and Day, 2022; Gaylord, Cowell, Hoepner, Perera, Rauh, and Herbstman, 2018; Rumbold, Giles, Whitrow, Steele, Davies, Davies, and Moore, 2012; Anastosio, Leventhal, and Amadon, 2022).

When the frequent moves occur from neighborhood to neighborhood, children may be most at risk because they are the least likely to stay long enough to experience the benefits of school-based and organizational interventions (Molborn, Lawrence, and Root, 2018).

Increased instability is related to other family factors. Families who are experiencing multiple housing moves also are frequently experiencing material hardship, economic strain, and other income-related challenges. Efforts to reduce housing instability may have a positive impact on children’s development and break the cycle of children’s environmental health disparities (Gaylord, Cowell, Hoepner, Perera, Rauh, and Herbstman, 2018; Fowler, McGrath, Henry, Schoeny, Chavira, Taylor, and Day, 2022; Anastosio, Leventhal, and Amadon, 2022).

- Receiving support like energy assistance and HUD-supported housing may help mediate the impact of housing instability and economic strain (Gaylord, Cowell, Hoepner, Perera, Rauh, and Herbstman, 2018).

- The direction of the moves also is crucial. Moves from advantaged neighborhoods to disadvantaged neighborhoods are related to more negative outcomes than when the moves occurred in other directions or within the same neighborhood (Molborn, Lawrence, and Root, 2018; Gaitan, 2019).

While research has indicated that housing instability can lead to negative impacts for children’s physical and social-emotional health, some studies found that homeownership and affordability were not strongly related to children’s health outcomes (Leventhal and Newman, 2010). It’s essential to note that home ownership may not be the solution to reduced housing instability and more positive child outcomes.

Recommendations

There are several key takeaways for communities and organizations related to supporting child development and academic success by providing more supportive housing environments:

- Support additional financial waivers and assistance for low-income families in need of housing support.

- Advocate and work for affordable housing and mixed-income neighborhoods.

- Establish connections between emergency shelters and early education settings.

- Establish connections between housing support, waivers, and early education support systems.

- Ensure that parents and families are connected to existing resources within the community that will help reduce material hardship, support housing stability, and easing economic strain of housing costs.

- Provide supports to families during pregnancy and infancy to increase housing stability.

- Encourage social support organizations and services to inquire about housing quality and stability to be able to recognize hardships and provide assistance.

- Encourage schools and early childhood education locations to provide additional supports and resources to children who have experienced housing instability.

- Advocate for housing policies that promote housing stability and encourage upwardly mobile moves for those who are interested.

Increase community understanding of the need for stable and quality housing to improve overall family well-being and child development.

Contact:

Bill Valladares

GaFCP Communications Director

404-739-0043

william@gafcp.org

Reg Griffin

DECAL Communications Director

404-656-0239

reg.griffin@decal.ga.gov

Follow us on Twitter: @gafcpnews

Connect with us on Facebook.

Bright from the Start: Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning (DECAL) is responsible for meeting the child care and early education needs of Georgia’s children and their families. It administers the nationally recognized Georgia’s Pre-K Program, licenses child care centers and home-based child care, administers Georgia’s Childcare and Parent Services (CAPS) program, federal nutrition programs, and manages Quality Rated, Georgia’s community powered child care rating system.

The department also houses the Head Start State Collaboration Office, distributes federal funding to enhance the quality and availability of child care, and collaborates with Georgia child care resource and referral agencies and organizations throughout the state to enhance early care and education.