Income Ladder Missing Some Rungs

Print This Post

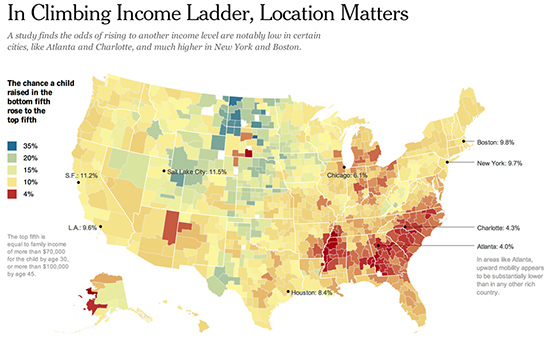

Check out this map from today’s New York Times. It shows that the odds of kids from lower-income households rising into the middle class are lower in Atlanta and other metro areas in the southeast than anywhere else in the country.

The map is part of a study by a team of top academic economists from Harvard and UC-Berkeley. The NY Times reports that this study contains some of the most powerful evidence so far about the factors that seem to drive people’s chances of rising beyond the station of their birth, including education, family structure and the economic layout of metropolitan areas. The researchers are looking at geographic and economic layout, and economic segregation for the first time.

Here are some of the highlights from the story:

The odds of rising to another income level are notably low in certain cities, like Atlanta and Charlotte, and much higher in New York and Boston.

The team of researchers initially analyzed an enormous database of earnings records to study tax policy, hypothesizing that different local and state tax breaks might affect intergenerational mobility.

What they found surprised them.

|

|

The researchers concluded that larger tax credits for the poor and higher taxes on the affluent seemed to improve income mobility only slightly.

All else being equal, upward mobility tended to be higher in metropolitan areas where poor families were more dispersed among mixed-income neighborhoods.

Income mobility was higher in areas with more two-parent households, better elementary schools and high schools, and more civic engagement, including membership in religious and community groups.

Regions with larger black populations had lower upward-mobility rates. But the researchers’ analysis suggested that this was not primarily because of their race. Both white and black residents of Atlanta have low upward mobility.

The authors emphasize that their data allowed them to identify only correlation, not causation.

Economists have found that a smaller percentage of people escape childhood poverty in the United States than in several other rich countries, including Canada, Australia, France, Germany and Japan.

Children who moved at a young age from a low-mobility area to a high-mobility area did almost as well as those who spent their entire childhoods in a higher-mobility area. But children who moved as teenagers did less well.

The comparison of metropolitan areas allows researchers to consider local factors that previous mobility studies could not—including a region’s geography. In Atlanta, the most common lament seems to be precisely that concentrated poverty, extensive traffic and a weak public-transit system make it difficult to get to the job opportunities.

Scroll on the interactive map to reveal the odds of kids rising out of poverty in your area, and read “In Climbing Income Ladder, Location Matters.”